Hannibal

Compiled from various sources. See citations.

Hannibal, the son of Hamilcar Barca,

(247 BC – c. 183 BC) was a Punic (See Carthage on the coast of North Africa

on the map below) military commander and politician, later also working in

other professions, who is popularly credited as one of the finest commanders in

history. He lived during a period of tension in the Mediterranean, when Rome

(then the Roman Republic) established its supremacy over other great powers

such as Carthage, Macedon, Syracuse and the Seleucid empire. He is one of the

best-known Carthaginian commanders. His most famous achievement was at the

outbreak of the Second Punic War, when he marched an army, which included war

elephants, from Iberia over the Pyrenees and the Alps into northern Italy.

During his invasion of Italy he

defeated the Romans in a series of battles, including those at Trebia,

Trasimene and Cannae. After the Battle of Cannae, Capua, the second largest

city of the Roman Republic, defected from the Republic and joined Hannibal.

Hannibal lacked the siege equipment necessary to attack the heavily defended

city of Rome. He maintained an army in Italy for more than a decade afterward,

never losing a major engagement, but never able to push the war through to a

conclusion. During that period, the Roman armies regrouped. A Roman

counter-invasion of North Africa forced him to return to Carthage, where he was

defeated in the Battle of Zama. The defeat forced the Carthaginian Senate to

send him into exile. During this exile, he lived at the Seleucid court, where

he acted as military advisor to Antiochus III in his war against Rome. Defeated

in a naval battle, Hannibal fled again, this time to the Bithynian court. When

the Romans demanded his surrender, he preferred to commit suicide rather than

submit.

Hannibal is universally ranked

as one of the greatest military commanders and tacticians in history. Military

historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge once famously called Hannibal the "father of

strategy", because his greatest enemy, Rome, came to adopt elements of

his military tactics in their own strategic canon. This praise has earned him a

strong reputation in the modern world and he was regarded as a "gifted

strategist" by men like Napoleon Bonaparte and the Duke of Wellington. His

life has also been the basis for a number of films and documentaries.

Hannibal began the most

significant part of his military career in Spain (Hispania) when he inherited

the command of the Carthaginian armies (221 BC) that his father and

brother-in-law had commanded. He

set off to conquer Rome in 218 BC. He fought his way through the northern

tribes to the Pyrenees (Northern Spain) and, by conciliating the Gaulish chiefs

along his passage, reached the Rh™ne River (See map below) before the Romans

could take any measures to bar his advance. Arriving at the Rh™ne in September,

Hannibal's army numbered 38,000 infantry, 8,000 cavalry, and 37 war elephants

(He was from Africa and thus elephants seemed like a good idea). This

Hannibalic invasion of Italy is called the Second Punic War. [See the map

below.]

Hannibal«s

route of invasion

Given by the

Department of History, United States Military Academy

He

engaged the Romans in numerous battles É.

thenÉ.

The Battle of Cannae

In the spring of 216 B.C.,

Hannibal took the initiative and seized the large supply depot at Cannae in the

Apulian plain. By seizing Cannae, Hannibal had placed himself between the

Romans and their crucial source of supply. Once the Roman Senate resumed their

Consular elections in 216, they appointed Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius

Aemilius Paullus as Consuls. In the meantime, the Romans, hoping to gain

success through sheer strength in numbers, raised a new army of unprecedented

size, estimated by some to be as large as 100,000 men.

The Roman and Allied legions of

the Consuls, resolving to confront Hannibal, marched southward to Apulia. They

eventually found him on the left bank of the Audifus River, and encamped six

miles away. On this occasion, the two armies were combined into one, the

Consuls having to alternate their command on a daily basis. The Consul Varro,

who was in command on the first day, was a man of reckless and hubristic nature,

and was determined to defeat Hannibal. Hannibal capitalized on the eagerness of

Varro and drew him into a trap by using an envelopment tactic which eliminated

the Roman numerical advantage by shrinking the surface area where combat could

occur. Hannibal drew up his least reliable infantry in the center with

the wings composed of his elite troops, the Gallic [Spanish and Gaulish] and

Numidian cavalry. [Livy called the Numidians the hands-down best horsemen of

Africa. They rode small, fast

Arabian horses without saddles or armor and only wielded a small shield, a

short sword and a spear or javelin.

They were fast, agile, and incredibly damaging to enemy order. They sowed chaos.]

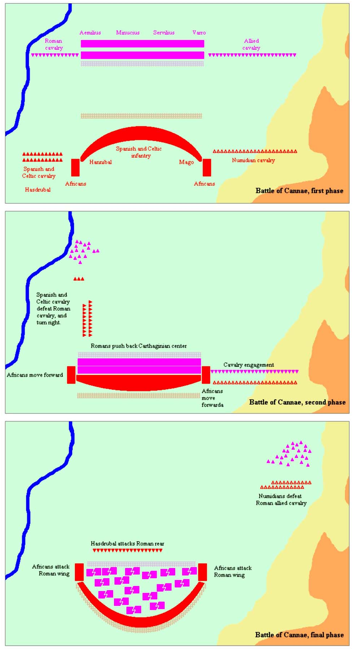

Initial

deployment and Roman attack. Romans

in red and HannibalŐs forces in blue.

Hannibal

intentionally put his weakest forces in the center. When they pulled back [see arrows on the diagram above], the

Roman forces followed.

The Romans

advanced into Hannibal's lines, which swung around them.

The Roman legions forced their

way through Hannibal's weak center, but the Libyan Mercenaries (labeled

"African Infantry" on the diagram above and below) in the wings swung

around and menaced the Roman flanks. The onslaught of Hannibal's mounted forces

was devastating, and Hasdrubal, the Carthaginian who commanded the left

(labeled "Spanish and Gaulish Cavalry" in the blue-lined boxes),

pushed in the Roman right and then swept across the rear and attacked Varro's

cavalry on the Roman left. Then he attacked the legions from behind. As a

result, the Roman army was hemmed in with no means of escape. [See the other set of diagrams at the

end of this page for a few more details on the battle tactics and the various

commanders.]

Destruction of

the Roman Army

The central

blue (HannibalŐs) forces pulled back and sucked the central Roman forces to the

right.

The result was

that the Roman forces were surrounded by HannibalŐs forces.

Both diagrams

courtesy of The Department of History, United States Military Academy.

Due to these brilliant tactics,

Hannibal, with much inferior numbers [about 55k vs 75k Roman troops (all

numbers associated with this battle are vague at best)], managed to surround

and destroy all but a small remainder of this force. Depending upon the source,

it is estimated that 50,000-70,000 Romans were killed or captured at Cannae (in

one day!). [The Roman historians Livy and Polybius variously claim that

50,000-70,000 Romans died with about 3,000–4,500 taken prisoner. The

fatalities for the Carthaginians amounted to about 6,000 men it has been

estimated.] Among the dead were the Roman consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus, as

well two consuls for the preceding year, two quaestors, twenty-nine out of the

forty-eight military tribunes and an additional eighty senators (at a time when

the Roman Senate was comprised of no more than 300 men, this constituted

25%–30% of the governing body). This makes the Battle of Cannae one of

the most catastrophic defeats in the history of Ancient Rome, and one of the

bloodiest battles in all of human history (in terms of the number of lives lost

within a single day). After Cannae, the Romans were not as enthusiastic in

challenging Hannibal in pitched battles, instead preferring to defeat him by

attrition, relying on their advantages of supply and manpower. As a result,

Hannibal and Rome fought no more major battles in Italy for the rest of the

war.

The effect on morale of this

victory meant that many parts of Italy joined Hannibal's cause. As Polybius

notes, "How

much more serious was the defeat of Cannae, than those which preceded it can be

seen by the behavior of RomeŐs allies; before that fateful day, their loyalty

remained unshaken, now it began to waver for the simple reason that they

despaired of Roman Power.". During that same year, the Greek cities in

Sicily were induced to revolt against Roman political control, while the

Macedonian king, Philip V pledged his support to Hannibal – thus

initiating the First Macedonian War against Rome. Hannibal also secured an

alliance with newly appointed King Hieronymous of Syracuse. It is often argued

that if Hannibal would have received proper material reinforcements from

Carthage he might have succeeded with a direct attack upon Rome. For the

present he had to content himself with subduing the fortresses which still held

out against him, and the only other notable event of 216 BC was the defection

of Capua, the second largest city of Italy, which Hannibal made his new base.

However, only a few of the Italian city-states which he had expected to gain as

allies consented to join him.

Hannibal and his army wandered

around Italy for about 15 years (218-203 BC) and wreaked havoc. Meanwhile

Carthage had been steadily declining in wealth and stature while Hannibal was

off warring in Italy. Rome had even conquered much of the Iberian penninsula

[led by Scipio Africanus] where Carthage had traditionally been very strong and

they conquered the extremely important city of Syracuse on the island of

Sicily. Finally Rome sent forces led by Scipio Africanus to attack Carthage

directly. This action forced Hannibal to leave Italy in order to defend his

African homeland. This time around

his famous tactics didn't work.

The Roman forces were much better seasoned and knew that Hannibal was a

tricky tactician. In the resulting major engagement (at Zamia in 202 BC –

Zamia or Zama is a bit inland from the city of Carthage.) Carthage lost

approximately 31,000 troops with an additional 15,000 wounded. In contrast, the

Romans suffered only 1500 casualties. The battle resulted in a loss of respect

for Hannibal by his fellow Carthaginians. It marked the last major battle of

the Second Punic War, with Rome the victor. Hannibal lost. In 201 he signed a peace treaty with

Rome and was dishonored and retired.

The conditions of defeat were staggering. Carthage gave its huge fleet of warships to Rome. They had to formally recognize the

Roman conquests of Iberian lands and they had to pay a huge sum of money in 50

annual installments to Rome.

Hannibal rebuilt his credibility

and rose in the political hierarchy.

Rumors claimed that he started thinking about another run at Rome and

that he started to negotiate with the Seleucid Empire (i.e., the

post-Hellenistic empire that controlled modern day Turkey, Syria, Palestine,

Iraq and Iran) for support. When

the Romans got wind of his supposed plans, they sent an investigative team and

Hannibal fled to the East, to Ephasus on the Ionian coast of Turkey and then to

Antioch (in modern day Syria). He

hung out with the Seleucid Emperor and advised him on military matters. He eventually was given command of a

Seleucid fleet, but was defeated in 190 BC and ended up in league with a rebel

Seleucid governor who set up in Arminia.

He fled again and ended up in the court of the king of Bythnia (a

province which contained the famous city of Nicaea... sort of close to modern

day Istambul). In 184 Hannibal,

commanding his fleet, had one last victory. In 183 BC (or 182 or 181 ... the sources are not clear)

Hannibal saw no escape from capture by the Romans and poisoned himself.

©

Jona Lendering for Livius.Org, 1995. Revision: 15 March 2008

Livy, The War with

Hannibal

Lendering, Jona,

"Hannibal," Livius: Articles on Ancient History, http://www.livius.org/ha-hd/hannibal/hannibal.html

Wikipedia

contributors, "Hannibal," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hannibal&oldid=317494691

(accessed October 4, 2006).